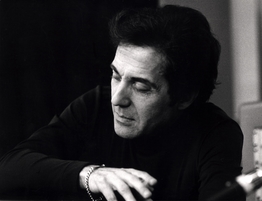

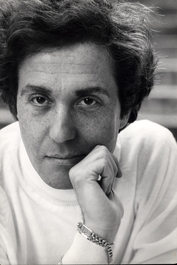

Aldo Ciccolini

News

Erik Satie, 150 years of the eccentric French composer par excellence!

Erik Satie: The Oldest of the Moderns

With his unfailingly immaculate detachable collar and his brilliant conversation, Satie delighted the salons of Parisian society and gathered around his bowler-hatted figure with umbrella several generations of musicians from Claude Debussy to Henri Sauguet. His personality quickly took precedence over his music in the public’s perception. Is the situation different 150 years after his birth? The 10-CD complete edition Tout Satie pleads in favour of the affirmative.

Satie was born at Honfleur on 17 May 1866. His mother was of Scottish origin, and his father was a shipping agent; they were Anglican Christians. Torn between Normandy and Paris, the family settled in Paris in 1870. Two years later, Satie’s mother died and his father placed the young boy into the hands of his parents. Six years later, in 1878, his grandmother was found dead on the beach in Honfleur, and so now the 12-year-old Satie returned to live in Paris with his father, who married a young pianist by the name of Eugénie Barnetche. There he took lessons in piano playing, standing out, despite some talent, as a bad student and displaying an equal dislike for his mother-in-law, the instrument and the music.

His disquiet did not prevent him from entering the Paris Conservatoire through a back door in 1879 but only two years elapsed before he escaped with a dismissal: “untalented,” grumbled his teachers, who nevertheless readmitted him to the respectable institution at the end of 1895. There is a somewhat comical trait about this coming and going, rather like a hesitating waltz, that presaged the start of something. In 1884, he composed what appeared to be his first piano piece with the simple title of Allegro - his teachers had been seriously mistaken when they thought the young man definitely had no future in music.

However, Satie decided to take up military service, a blunder that he was soon able to rectify when he developed a serious congestion of the lungs brought on by a deliberate exposure of his naked torso to the cold. It was now 1887, Satie was 21 and had settled in Montmartre. He spent time in cabarets, rubbed shoulders with Verlaine and Mallarmé, composed his Ogives written without bar lines, a style that was to remain one of his signature characteristics, as well as three pieces for piano which were to become the sonic symbol of his work: the Gymnopédies.

Then came the decisive encounter. At the Chat Noir Café-cabaret, he became friendly with Claude Debussy. The first years after 1890 were blessed times: Satie became the "official" composer and choirmaster of the Ordre de la Rose-Croix Catholique. He started to gain renown and he took Debussy along with him on his sweet pseudo-mystical journey.

Faith but also love revealed themselves to him in the features of Suzanne Valadon: she was to sketch her lover with a beard and long hair in a touching portrait. The end of this relationship, unequally shared, was to leave Satie far more broken-hearted than he wanted to admit to himself. Something snapped suddenly in him. Vexations – a short and dry piece "to play 840 times in a row" – might have been a vain outlet.

Satie’s soul was dead but the composer in him continued to live for 32 more years. Obdurately self-willed, his multi-faceted oeuvre was to be characterised by a modal grammar and white colour that lay outside any established trends, but created a trend of its own that was to marginally influence young people: it was to be a constantly present "elsewhere" in the musical landscapes that followed in Paris at the start of the 20th century.

Meanwhile, in 1895 he received a small inheritance that quickly melted away between his fingers, dispersed in editions of his music. It was the only real moment of relative opulence in a life that was soon reduced to poverty, forcing him to remain a cabaret pianist for a long time and attend social dinners in town by paying with his fine words.

So it was that he would go from the cafés in Montmartre to the tiny room in Arcueil where he finally settled in 1897. Here he composed his works ranging from melodies that he called "thorough rubbish", such as Je te veux, to piano pieces with convoluted and hilarious titles such as Embryons desséchés (“Desiccated Embryos”) and other Peccadilles importunes (“Tiresome Pranks”). His scores abound with performance markings swinging between poetic and humorous comments that are intended for the sole enjoyment of the interpreters.

Even so, Satie felt that his compositional technique was not yet fully fledged, and so in the autumn of 1905 he became a pupil of Vincent d’Indy and Albert Roussel at the Schola Cantorum. His friends thought that he was having one of his funny turns, but under his "good masters" Satie blithely learned the strict academic technique of counterpoint. He dressed it up in his own way and Debussy made fun of it by calling him "Mister Counterpoint". So now he was a perfect musician! Was this necessary for his music?

The First World War now introduced Satie to a new generation. In 1915, through Valentine Gross he met Jean Cocteau, who became a kind of mascot for him. Undoubtedly the poet had some affection for the future composer of Parade, although correspondence that is often coloured with spiteful remarks and clashes over "matters of principle" reveals that the idyll was more often than not a bitter one. But this did not really matter in the long run, since on the one hand Satie became the idol of the young musicians – it was around his small goatee beard that le Groupe des Six was gathered together, he became both their backbone and their catalyst – and on the other hand he also became the composer of Parade.

Up to now, the musician of Arcueil had carved his own way mainly with the piano. Parade inspired the fortification of his art. Could Roussel have ever imagined that his orchestration pupil would write a ballet with a siren, a gun and a typewriter?

Parade was Cocteau’s conception – he "sold" the design of the stage set to Picasso before Satie had composed a single note – but it was Satie’s music that was to create the ‘scandale’ that ultimately spelled a glorious success but also eight days in a detention cell for having called the critic Jean Pouiegh an "unmusical ass". And finally on this subject of Parade, Guillaume Apollinaire should have the last word: in the premiere’s programme, he noted the "surrealist" quality of the show.

With this ballet, Satie had taken a leap forward. Well aware of the journey he had taken from the Montmartre cabarets to the European avant-garde, in 1919 he became friends with Tristan Tzara, Man Ray, André Derain, and Marcel Duchamp.

There was not a single musician friend on the horizon: instead he formed an allegiance with the Dadaists. Taking sides with Tzara in 1922 during the famous discord between the poet and André Breton, he had become so indispensable to the futurist movements that Breton, despite his anathema, decided not to sever ties.

In the short time that Satie had left to live, such notoriety did not bring him the financial relief that he could have hoped for. Poverty persisted, but his music made a quality out of it: the whiteness of timbre, the sparseness, the economy, the writing so modest that it became a quasi-abstraction: these were the culminating attributes of what constitutes after Gymnopédies and Parade his third masterpiece.

In 1918, The Princess of Polignac commissioned him to write what would become Socrate, a triptych full of bare and unchecked emotion. Probably for the first time, Satie was completely happy with his work. The laughter he had to endure at the premiere of the orchestrated version in 1920 left him speechless but yet did not destroy his will to compose.

With Jack in the Box, and Mercure, he sought in vain to recreate the success of Parade. He was not left without friends: in 1923 a group from the School of Arcueil brought him a few young people that were followers of Max Jacob, among them Henri Sauguet and Roger Désormière.

In January 1925, Satie fell ill; it was to be a fatal disease. What a surprise for Milhaud when he entered Satie’s Arcueil lodging for the first time after his death to find two pianos tied together by a rope and the room full of unsealed letters testifying to a life of darkest misery. Here, after the composer’s death, they miraculously found Geneviève de Brabant, a score Satie had pretended to have lost– a final jest of his destiny unless, in keeping with his fabled hoaxing, he might have quietly put it away pending its improbable survival.

Jean-Charles Hoffelé (Translation: Michèle Fajtmann).

The 150th anniversary 10-CD boxed set Tout Satie! is out now.

Limited-edition Erik Satie album to be released on vinyl for Record Store Day

An exclusive re-release for Record Store Day 2016 (16 April), this LP of Gymnopédies, Gnossiennes and other piano pieces by Erik Satie marks the 150th anniversary of the eccentric composer's birth.

It also salutes Aldo Ciccolini, the Italian-born pianist who launched the Satie ‘boom’ when this album first appeared in 1956.

Whether enigmatically serene, irresistibly charming or anarchically witty, the maverick French composer’s miniature pieces remain astonishingly original. His whimsical avant-garde view of the world has inspired artists and musicians from Jean Cocteau to John Cage to John Cale.

At every moment on this recording, Ciccolini makes clear why, when he died in February 2015, The New York Times described him as “a champion of Erik Satie”.

The limited-edition release will be available in a pressing of 1,000 copies only.

Three leading pianists pay tribute to Aldo Ciccolini

JEAN-YVES THIBAUDET

I met Aldo Ciccolini when I was 17, and for me he really was the kind of teacher we all dream of, the kind we all hope to be lucky enough to meet at some point in our lives.

He taught me the piano, of course, but his teachings went way beyond music; he was universal. His lessons weren’t just piano lessons, they were lessons in living. People so supremely cultured, so at ease in every possible field, are very rare nowadays. His considerable experience of professional music-making has also been a great inspiration to me.

NICHOLAS ANGELICH

Aldo Ciccolini has truly helped me to become myself. At age 13, I arrived from the United States and entered his class at the Paris Conservatoire. But it was only when around my thirties that I realised how much he had influenced me.

Every Tuesday and Friday between 2pm and 8pm we would meet Aldo. Not only to perform, but also to listen to one another. It was almost like a concert performance and not just a lesson in the traditional sense. Besides his comments, he took his part in the event by playing for us himself. It was a privilege to share his experience as a musician and to discover such an extensive repertoire ranging from Scarlatti to Rachmaninov.

During these afternoons spent in his company, he used to recall musicians he deeply respected: Artur Schnabel, Wilhelm Backhaus or Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli. He insisted on the fact that as musicians, we had a huge responsibility towards the works we were playing: respecting the composer’s intentions as expressed in the musical score, showing great care for quality of sound and harmonics, and avoiding all cheap effects.

Today, having become a professor myself at the Conservatoire, I try in my own way to pass on these musical and, in a sense, philosophical principles.

PHILIPPE CASSARD

For twenty years, until about 2000, I was unable to go to any of Ciccolini’s recitals. I had memories of him as a virtuoso of distinction, elegant, yet with a tinge of distance due to the restraint he observed even in Liszt’s epic showpieces, of which he was a justly celebrated interpreter.

Then, in 2001, quite probably prompted by my friend Jean-Yves Thibaudet, I invited Ciccolini to the Estivales de Gerberoy, a festival I started in Normandy, not far from Rouen. Right from the outset I was touched by his kindness and straightforward friendliness (even though we didn’t know each other, as soon as we got talking on the phone he said we should use the familiar tu, not the formal vous, because ‘we are colleagues’), then I was completely blown away by the beauty, the breadth, the risks he took during the recital.

In a number of rarely heard works (a Clementi sonata, Poulenc’s Napoli, the Verdi/Liszt Aïda finale) his tone ‘opened up’ like a bottle of exquisite wine after fifty years in a cellar, his cantabile soared with infinite generosity and flexibility, and the lofty virtuosity of the past became purely abstract, even more impressive because of the subtlety, depth and aptness of the musical discourse. It was like hearing once again the leonine touch of my teacher Nikita Magaloff, together with the exuberance, the pugnacious, almost frenetic joy that are the signs of the true epicurean, putting the younger generations to shame!

These three tributes were collected in 2010 for the release of Aldo Ciccolini's complete recordings 1950-1991.

Aldo Ciccolini in his own words

The Well-Tempered Keyboard

For the 2010 re-release of all his EMI recordings, now an integral part of the Warner Classics catalogue, Aldo Ciccolini agreed to say a few words about the composers with whom he maintained especially close links. With his sharp esthetic sense which, like André Gide, he views as subservient to moral considerations, this immense musician gave his subjective history of the piano with complete spontaneity and delightful digressions.

Interview with Olivier Bellamy

Translation: Peter Byrd

Bach and the harpsichord

I studied the harpsichord with a pupil of Wanda Landowska’s who knew Bach inside out and opened up a whole world (Rameau, Couperin) I did not know at all. The richness of the musical language impressed me, even though I have recorded very little of this music. I have played very little Bach in my life. The sound of the piano does not seem to me to suit the Well-Tempered Keyboard, while the Chromatic Fantasy fits it very well. As a general rule, I don’t think one should play Bach staccato. Some of the preludes call for legato and quite a few of the fugue subjects are not well served by a highly detached articulation aimed at separating the sounds.

Scarlatti

I find him interesting in the extreme; his sonatas are the work of a jovial troublemaker. Harmonically, they must have seemed scandalous at the time. The harpsichord is too fragile to do justice to his unbridled inventiveness and his unique blend of tenderness and fierce irony. Scarlatti’s writing is incredibly pianistic and very virtuoso, but it never descends into the gratuitous virtuosity you find in certain pieces that are completely devoid of music, like Balakirev’s Islamey, for example. Certain composers could not resist the temptation to defy the laws of nature. Even Brahms fell into that trap in his Variations on a Theme by Paganini, which are extraordinarily stupid. Paganini’s Second Concerto contains some quite pointless difficulties and not all the notes in Rachmaninov’s Third Concerto are of equal interest. In the world of opera, voices have been ruined by certain parts (Cherubini’s Medea). In the piano repertoire, difficulty for its own sake is death to musical taste.

The Russians

Russian music has an indefinable charm made up of nostalgia, chronic dissatisfaction, tenderness and haunting sadness which blends in with the Slav temperament. I have always enjoyed playing Rachmaninov’s Second Concerto very much, even though a great deal of strength is required to match its thickly scored orchestra. I have played it with Yannick Nézet-Séguin, who is set to be the Carlos Kleiber of tomorrow.

Prokofiev and Shostakovich

Prokofiev is unpredictable: you never know what he is going to write three bars later. This was a man who had a very sound grasp of musical structure. One can’t say as much of Shostakovich, who I will never forgive for saying that Scriabin ‘dishonoured’ Russian music. Some of his Preludes and Fugues are excruciatingly ugly – not in an intelligent way; it’s an ugliness born of ignorance.

Spanish music

This is the most beautiful folk music in the world, and the only one I genuinely admire. Albeniz’s music is just as popular as it is refined. And what richness! ‘He simply throws his music away’, Debussy used to say. I have both performed and recorded Iberia. It is incredibly difficult and very well written throughout. It brings back to me the intense feelings I experienced when I first went to Granada. I hung about in gypsies’ caves in the hope that their ill temper would give way to a desire to dance. You had to wait patiently until the look on their faces changed and became electric. Singing and dancing flamenco helps you understand Albeniz’s music. Naples, where I was born, was occupied by the Spanish for three centuries and our folklore is saturated with their influence. The most beautiful Neapolitan songs have Spanish rhythms; many of them are like habaneras.

Grieg

He is more loved than admired. I love and admire his music madly. He was an excellent pianist, who championed his concerto himself. Even Debussy, who was very hard to please, recognised the quality of his works.

Debussy and Ravel

Claude Debussy is still the greatest musical enigma that has ever existed. You never get to the bottom of his music. That is perhaps why he will never be forgotten: people will never give up trying to make sense of him!

Ravel is an extraordinary magician, but his genius is less mysterious. Debussy never fails to surprise you. The titles of his Préludes (added in later) do not resolve the fundamental ambiguities of these pinnacles of the piano repertoire. Voiles, for example, is impossible to pin down or define. And Une barque sur l’océan comes across like music for a strip-tease. A musician could spend years trying to understand Debussy’s Préludes. I’ve been at it for sixty years now and I still approach them as if it were the first time, as if nothing had been finally sorted out for me. And it must also be said that his music has a charm that is quite indefinable. Sometimes you can be struck by something that suddenly touches you very deeply without understanding why. I listen to Pelléas et Mélisande (Roger Désormière’s recording) at least twice a month with the score on my lap. I feel an aesthetic and emotional need for it.

Ravel’s two concertos are masterpieces. The solo part of the Concerto in G fascinates me. Ravel said that when writing each note he had no idea what the next one would be. And yet it all seems to be based on the strictest logic.

Mozart

I adore Mozart. The Theme and Variations he wrote when he was eight is already perfect. He needed time. He knew what his potential was,

but he did not have all the time he needed to express everything he had to say. When performing his music, you are constantly exposed. It is like a diamond in which the slightest impurity destroys everything.

Liszt

He never hurt a pianist’s hand. He is a reliable, faithful and loyal friend. I recorded the works Georges Cziffra did not want. He turned down EMI’s request for a recording of the Harmonies religieuses et poétiques. In my view this is a prophetic masterpiece, which has a dark side to it. Pensée des morts was written at a time when Liszt was going through a doubt-ridden crisis. And the last piece in the cycle, Cantique d’amour, is not religious in spirit at all. Many of Liszt’s works still need to be discovered… Les Années de pèlerinage is a very densely written work. I love Au bord d’une source, but Cloches de Genève a bit less, though it is also music of a very high standard. I worked on about ten of Liszt’s lieder with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf. Two or three of them struck me for their beauty.

Chopin

I have always avoided a certain way of playing Chopin that I find improper. He deserves our love, but also our respect. We should guard against the distasteful habit of using him as a vehicle for expressing our own little woes.

We must remember that Chopin was above all a great human being. People have wanted to imitate Alfred Cortot, who was unique. The fact that Chopin was ill is no reason to portray him as a sickly little girl. His Third Sonata and even the Second are works by a man in full possession of his resources. To play Chopin hysterically is to turn him into something he was not. But to perform him in too ‘moral’ a manner is a mistake. All composers are amoral. Moral music is a form of boredom.

Stravinsky

Music can suggest just about anything, but it can never make statements. To believe it can is to put music on the path to decadence. That is why I have always found Stravinsky unbearable. He is a show-off, just like Picasso, who indulged in provocation to earn ever more money. I have more respect for Dalì (his Christ in space has influenced me a lot) because I find him more sincere than Picasso. Picasso changed styles out of sheer opportunism. Liszt was just as sincere in the B minor Sonata as he had been earlier in the Hungarian Rhapsodies.

Schubert

If only Schubert had lived as long as Saint-Saëns or Liszt! Leibowitz once phoned me in the middle of the night to ask me to come and sight-read something. At 2 in the morning I took a taxi to the Latin Quarter. There were about ten people in his flat. I looked at the music on the piano to try and work out what had stimulated such excitement. It was a march by Schubert. As I played through it I came across eleven bars that were practically atonal. Schubert had the knack of modulating into very far-off keys as if it were perfectly natural. His music is not easy to play, but it is so beautiful.

It is hard to say who he was. Most of the portraits show him as either chubby with glasses or handsome like James Dean.

Schumann

I have always loved Schumann, his tenderness and sincerity.

Saint-Saëns

Everything came so easily to him that he did not work hard enough on his thematic material.

Massenet

He was a magnificent pianist. Liszt admired him a lot. I love Massenet’s operas. They don’t set out to make you break down and sob: they bring tears to your eyes.

Satie

EMI’s Artistic Director wanted to bring out a homage to Satie, who was not very popular, and suggested I record some of his music. ‘If we sell 200 copies, it will be a miracle’, he warned me. A week after the release 4000 had been sold – a triumph! So we recorded the complete works and Satie became famous all over the world.

It is mystical music whose apparent simplicity is deliberately intended to ward off mere virtuosos. I am passionately fond of Satie as a person. One day he played for the Princess de Polignac and refused the fee she tried to give him. He earned his living playing in piano bars. ‘Here, I play for pleasure’, he told the Princess. And he went back home to Arcueil on foot. A saint! And such an original mind. A person like that could only have been born in France!

Aldo Ciccolini has died in Paris at the age of 89

“Every day I work, and sometimes through the night. I have the great – and dreadful – fortune of being an insomniac. For me, sleep is a figment of the imagination. I am now awaiting the eternal sleep, and just enjoying the moment, I prefer to keep working.”

Aldo Ciccolini, November 2014

It is with great sadness that we report the death of Aldo Ciccolini, at the age of 89. In 1950, as victor of the 1949 Marguerite Long Competition, the 25-year-old Ciccolini recorded his first 78 RPM devoted to Scarlatti, the beginning of 40 years of outstanding collaboration with the French EMI, for which he pioneered the complete piano works of Satie, Séverac, the piano music of Massenet and many others, before crowning his recording career with the complete piano works of Claude Debussy.

Aldo Ciccolini, though born in Naples, now holds an eternal place at the very summit of French pianism.

Pianist Aldo Ciccolini wins the ICMA Lifetime Achievement Award

Related releases