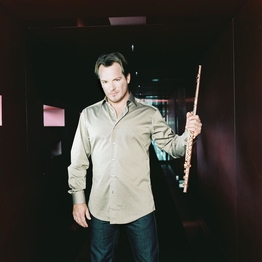

Emmanuel Pahud

News

Mozart & Flute in Paris set to arrive in July

This double album, Mozart & Flute in Paris, brings together nine captivating works, all with their origins in Paris, which feature a solo flute. Emmanuel Pahud is joined by his colleagues from ‘wind supergroup’ Les Vents Français – oboist François Leleux (here also conducting the Orchestre de chambre de Paris), clarinettist Paul Meyer, bassoonist Gilbert Audin and horn-player Radovan Vlatković – and by Belgian harpist Anneleen Lenaerts, who has starred on three Warner Classic releases.

“The pieces on this album represent different golden ages of the flute,” says Pahud. The earliest, dating from 1778 are two concertante works that Mozart wrote on his third and final visit to Paris, at a time when the flute was a fashionable instrument in the homes of the aristocracy and bourgeoisie. The newest, premiered in 2014 by Pahud and the Orchestre de chambre de Paris, is Dreamtime by Philippe Hersant, which evokes the creation story of the Australian Aboriginal culture. (Dreamtime was also the title of a Warner Classics album released by Pahud in 2019; it features another piece that draws on Aboriginal philosophy, Toru Takemitsu’s I hear the water dreaming.)

France has had a special relationship with the flute since the time of Louis XIV and his court composer Jean-Baptiste Lully. In the latter part of the 19th century the flautist Paul Taffanel (1844-1908) became a prominent figure, notable for the technical and stylistic sophistication of his playing; Professor of Flute at the Paris Conservatoire from 1893, he is seen as the father of the modern school of French flute-playing. Emmanuel Pahud studied the Paris Conservatoire, where François Leleux was among his contemporaries; Paul Meyer and Gilbert Audin are also among its distinguished alumni. Composers in Taffanel’s sphere of influence are represented by Saint-Saëns (three pieces, including the Tarantelle op 6, which calls for Pahud to duet with Meyer), Fauré, Chaminade (one of the most successful female composers of her time), and Poulenc (his flute sonata in an orchestration by the British composer Lennox Berkeley, who studied with the great French teacher Nadia Boulanger). When talking about all these pieces, Pahud enthuses about their colour, their luminosity and the memories they evoke for him.

It was the flautist Johann Baptist Wendling, a member of the pioneering orchestra at the court of Mannheim in Germany, who encouraged Mozart to seize the professional opportunities offered by Paris. Within two weeks of Mozart’s arrival in the city in 1778 (he had previously visited in 1763 and 1766), he was commissioned to write the Sinfonia Concertante for Flute, Oboe, Horn and Bassoon in E-flat major. Wendling was to be among the soloists, but for various reasons the piece was never performed. The score was lost, but a (controversial) version using clarinet rather than flute re-emerged in 1870, and in the 1980s the American musicologist Robert D Levin prepared the authoritative edition that is used on Mozart & Flute in Paris.

Wendling also played a role in the genesis of Mozart’s Concerto for Flute and Harp, since he introduced Mozart to his talented amateur pupil Adrien-Louis de Bonnières, Duc de Guînes. The Duke’s daughter, Marie-Louise Philippine, played the harp, and also took composition lessons with Mozart. If the beguiling combination of flute and harp now seems natural to us, in 1778 it represented an innovation. Mozart succeeded in writing a concerto that exemplifies the grace and elegance we associate with the aesthetics of the later 18th century.

Emmanuel Pahud and Daniel Barenboim collaborate on Warner Classics’ final Beethoven release of the year

Daniel Barenboim and Emmanuel Pahud both hold important posts in Berlin – Barenboim as General Music Director of the city’s Staatsoper Unter den Linden and Pahud as Principal Flute of the Berliner Philharmoniker. This programme of Beethoven chamber music with flute was recorded in June 2020 in Berlin’s newest concert hall, the elliptical 700-seat Pierre Boulez Saal, designed by Frank Gehry, which Barenboim inaugurated in 2017. In July 2020, he and Pahud made international headlines with Distance/Intimacy, the 10-concert festival of new music they staged in the hall, and which they had specifically conceived for online consumption under pandemic conditions.

This Beethoven album is Warner Classics’ final new release for the composer’s 250th anniversary year. Barenboim – here playing the piano – and Pahud are joined by four other distinguished musicians: the violinist Daishin Kashimoto, who is First Concertmaster of the Berliner Philharmoniker; the viola player Amihai Grosz, formerly of the Jerusalem Quartet and now Principal of the Berliner Philharmoniker’s viola section; Sophie Dervaux, who is Principal Bassoon of the Wiener Philharmoniker, and flautist Silvia Careddu, formerly Principal Flute of the great Austrian orchestra.

The programme comprises charming works from the earlier years of Beethoven’s career: from the mid-1780s, the Piano Trio WoO 37 for piano, flute and bassoon in G Major; from 1792, shortly before Beethoven left Bonn to live in Vienna, the Allegro and Minuet WoO26 for two flutes in G Major; from around 1800, the Serenade op 25 for flute, violin and viola in D Major, and from 1802, the Sonata No 8 Op 30, No 3 in G major – in fact composed for violin and piano, but here arranged by Emmanuel Pahud for flute and piano.

Emmanuel Pahud and Alexandre Desplat reimagine Oscar-winning scores

A supreme instrumentalist, flautist Emmanuel Pahud, takes the music of an Oscar-winning film composer, Alexandre Desplat, beyond the cinema.

Airlines is entirely devoted to world premiere recordings – of original concert works and of reimagined versions of Desplat’s film scores, including his Oscar-winners The Shape of Water (2018) and The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). Emmanuel Pahud is accompanied by the Orchestre National de France, conducted by Alexandre Desplat himself.

The release of Airlines comes soon after Desplat’s nomination for yet another Oscar, this time for Little Women, directed by Greta Gerwig. It also includes adaptations of his scores for Girl with a Pearl Earring (the film which brought the French-born composer his major international breakthrough in 2003), for Birth (2004) and for Lust, Caution, directed by Ang Lee and released in 2007.

The album complements these cinematic projects with works that evoke images in the mind rather than on the screen. One of these is a solo piece with the punning title Airlines – referencing both air travel and the flute as a wind instrument; it was premiered by Emmanuel Pahud in 2018. Another is a three-movement Symphonie concertante which carries a more familiar musical name: Pelléas et Mélisande. Here, Desplat follows Debussy, Fauré, Sibelius and Schoenberg in drawing inspiration from Maurice Maeterlinck’s haunting symbolist play, first seen in 1893. Desplat’s work was first performed, in France, in 2013, and he approached Emmanuel Pahud about it soon afterwards. The two musicians then met in Los Angeles, when Pahud was visiting the city on tour as principal flautist of the Berliner Philharmoniker. As he says: “I had told Alexandre how beautiful I found the ideas and themes [in the piece] … The idea of working together developed quite naturally. As it happened, I had been looking for an opportunity to collaborate on something beyond the normal concert format.”

He and Desplat collaborated closely on the adaptations of the film scores, a musical process that Pahud describes as delicate, since the music needed to be ‘repurposed’. It no doubt helped that Desplat has a special affinity with flute. The Paris-born composer has said that “it took me a while [as a child] to find the instrument that I liked, that would become my instrument. Because an instrument is an extrapolation of your own body, but also of your soul.” Desplat started with piano and cornet, but things did not go well. Then: “Suddenly, there was this instrument, the flute that I could immediately play. It was just … obvious. This instrument was made for me.”

For the adaptation of Girl with a Pearl Earring it was a matter of expanding a flute presence that was already prominent in the film score, but the music of both The Grand Budapest Hotel and The Shape of Water needed more substantial rethinking. For Lust, Caution the flute takes over lines originally conceived for violin. It so happens that the producer of Airlines is a violinist: Dominique Lemonnier, also known professionally as Solrey. As Alexandre Desplat (who is her husband) explains: “Solrey’s artistic guidance proved invaluable when it came to choosing the scores and to finding a balance between homogeneity and diversity. Her insights as a musical interpreter were of crucial value.”

Desplat, who studied in both France and the USA, and whose teachers included the modernist Iannis Xenakis, provided some valuable insights of his own in an interview with Forbes magazine. Discussing his working methods and inspiration, he said: “Creatively, I always have to take a deep breath and jump into another project that has nothing to do with the previous one. That’s the only way I can sustain the obsession or love that I have with a couple of chords or melodies or certain orchestrations without it all sounding the same …I don't know what influences me, I really have no idea, because I don't listen to music much. When I travel around I listen to music from South America, Brazil, Africa, Greece and also contemporary concert music, contemporary opera and chamber music. Those are the things I think that nourish my work most of all, but I don’t listen to them a lot. I do that more often than I listen to pop songs, but I love U2 and some rappers like Common.” For Alexandre Desplat, with music, the sky is the limit.

Emmanuel Pahud announces a dreamy and expressive next album

Emmanuel Pahud, with Ivan Repušić, Principal Conductor of the Munich Radio Orchestra, has dreamed up an unpredictable and spellbinding programme of music for flute and orchestra.

Dreamtime ranges wide both culturally and chronologically, embracing composers from Austria, Germany, Italy, Japan and Poland, and leaping from Mozart (Andante in C) to the early 20th century for works by Carl Reinecke (Concerto in D) and Ferruccio Busoni (Divertimento) and then forward to the 1980s and 90s for music by Tōru Takemitsu (I hear the water dreaming) and Krzysztof Penderecki (his seven-movement flute concerto).

“Rather than trying for stylistic or chronological consistency with this album,” writes Emmanuel Pahud, “I wanted to bring together concertante works which illustrate beautifully the power of dreams and of the unreal, as well as the strength of their composers’ personal Romantic visions. Writing and creativity were often a way of transcending the reality of their existence, and of expressing and giving form to their most personal, spiritual or dreamlike visions.

“Exploring the vast flute repertoire over the past 40 years has led me to appreciate the flute’s spiritual dimension,” he continues, “and I have come to realise the extent to which this was significant for composers. Thanks to its evocative power and the evanescent quality of its sound, the flute was a unique tool for them throughout various eras of music – as a solo instrument and in chamber music, of course, but also within the orchestra.

“In the pieces I have chosen, the human being’s inner world – secret by definition, a nucleus polarised against the rest of the world – is expressed delicately through dreams. We are in a dimension in which imagination is woven together and then unravels, which is populated by incantations and prayers, and where desire is roused by fantasy…”

It is the two most recent works on the programme which most explicitly make a connection with other levels of perception. The textures and timbres of the closing pages of Penderecki’s concerto evoke the total lunar eclipse which was underway as he composed them in December 1992, while Takemitsu’s I hear the water dreaming, first performed in 1987, was inspired by the beliefs of the Aborigines of Australia: Dreamtime, or Tjukurrpa, is a central philosophical concept that encompasses the creation of the world.

Pahud, who is artist-in-residence with the Munich Radio Orchestra over the 2019-20 season, sets great store by his collaboration with Ivan Repušić, praising his attention to detail and his capacity to spin out long phrases. As a conductor with substantial experience of working with singers in opera, he also understands the way wind players breathe – a great asset when it comes to capturing what the flautist calls “the dreamy, cantabile, expressive, wholehearted spirit of all these works”.

Vote now and have your say in the BBC Music Magazine Awards!

The shortlists for the 13th annual BBC Music Magazine Awards, the only classical music awards in which the main categories are voted for by the public, have been announced. A jury of expert critics selected this year’s 21 nominees across seven categories from over 200 longlisted recordings reviewed in 2017 by BBC Music Magazine, the world’s best-selling classical music monthly. The public vote is now open at the magazine’s website.

The many distinguished and varied nominees include, in the Opera category, the epic recording of Les Troyens, hailed the new reference recording and topping many Best of 2017 lists including The New York Times, The Guardian and the Chicago Tribune, thanks to its impressive orchestral and choral forces and an all-star cast headed by Joyce DiDonato, Marie-Nicole Lemieux, Michael Spyres and Marianne Crebassa.

'[Conductor John] Nelson drives the drama with unforced tempos but ample theatrical vitality. Spyres...sings with lyrical grace and spirit...Joyce DiDonato sings Dido with characteristic security and expressiveness,' opined BBC Music Magazine in its five-star review.

Flying the French flag in the Chamber category is the sensational team featuring Renaud Capuçon (violin), Edgar Moreau (cello), Emmanuel Pahud (flute) and Bertrand Chamayou (piano) in these mercurial Debussy sonatas - charming one moment, sensual the next. The French critics called the six players a 'supergroup', while BBC Music Magazine noted that 'a sense of joy in collegial music-making pervades these performances. Unlike many, violinist Renaud Capuçon and pianist Bertrand Chamayou and their colleagues do not avoid the vein of sensual passion that glows beneath Debussy's perfectionism...Perhaps the finest all is the beautiful balance of elegiac tone that thins out of the Sonata for Flute Viola and Harp.'

The Concerto category also features French harpsichord firebrand Jean Rondeau on the album Dynastie, with intensely intimate, energised performances of concertos by Bach and sons. 'His spirited and eloquently ornamented playing serves the music of JS Bach and three of his sons uncommonly well,' declared BBC Music Magazine.

There are seven categories open to the public vote: Orchestral, Concerto, Opera, Choral, Vocal, Chamber and Instrumental. Audio excerpts are available on the voting site, and all UK voters will be entered into a draw to win copies of the nominations.

The winners of the Awards will be announced at a ceremony on 5 April at Kings Place, London. In addition to the public awards, there are four jury awards: Premiere Recording, Newcomer of the Year, DVD of the Year and Recording of the Year.

See all the nominees and have your say now!

Emmanuel Pahud on why the flute concertos of C.P.E. Bach are so gutsy 1

At the court of Frederick the Great, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach was free to question the world. A conversation with Emmanuel Pahud on courtly customs, innovations and revolutions.

“There’s a new beginning in the music of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach.” When Emmanuel Pahud speaks about C.P.E. Bach, he likes best to talk about what he hears: “Physical music that doesn’t unconditionally follow the dictates of beauty, that experiments, that stirs up, that grates, that’s virtuosic — that storms and stresses at every moment and everywhere. In Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach’s music we hear that, in reality, the scene at Sanssouci was part of a new beginning, a world in upheaval.

"Frederick revolutionised Prussia, its politics, its military and its arts — but in the end he himself belonged to a species that was already becoming extinct. It is this premonition that can be heard in the music of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: everything is in flux; everything is extreme. In fast movements, he races as if striving to take flight into new worlds, while his slow movements are marked by incredible drama and depth.”

Time and again in his recent albums, Pahud has played the part of curious music historian, studying the music at the Sanssouci court (The Flute King) and then the sounds of the French Revolution. He also regards music as a contemporary view of the spirit of an earlier age.

His new album of three flute concertos by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach is the logical consequence of his explorations. Emanuel, second surviving son of Johann Sebastian Bach (Georg Philipp Telemann was one of his godfathers), was appointed chamber harpsichordist at the court of Frederick the Great in 1741.

“It’s interesting that Bach didn’t always toe the musical line at court,” says Pahud, “and I’m sure that wasn’t his concern: Bach went farther than Quantz, was more radical, and showed less consideration for his ruler’s tastes. Even the simplified royal version of his flute concertos overtaxed Frederick the Great.”

In his music, Bach combines the world of the court with that of the people — and he does this by fleeing from both realities and inventing a new and different world. He serves neither the powdered wigs nor the struggling multitudes, but instead he creates new, musical visions.” That is also why the composer is hard to pigeonhole for flautists. “Sure, he lived in the Rococo”, says Pahud, “but in his music we already hear the beginning of Romanticism, of Storm and Stress (Sturm und Drang), the urge to break away that represents the basis for Beethoven’s later unshackling.” The anticipation of historical periods also plays a role here for Pahud: “It was probably clear to Carl Philipp Emanuel that the Prussia of his masters was coming to an end, that the yearning for a new, republican Germany was already on the horizon.”

In this recording Pahud is once again working with trusted partners, conductor Trevor Pinnock and the Potsdam Kammerakademie. “Pinnock has always been a leading figure”, says Pahud, “not least for his legendary Bach recordings with flautist Jean-Pierre Rampal. He knows this period inside and out. He’s worked so long and hard on Johann Sebastian Bach, and in our collaboration on the court of Frederick we’ve learned from each other in dealing with both the sensual and intellectual aspects of the music.

"Meanwhile we’ve developed a kind of joint musical mind: a family which has enabled me to discover so many new things, and an environment in which interpretation becomes something totally natural.” Pahud is especially enthusiastic about “the physicality of Pinnock’s sound, that he’s not above getting his hands dirty and letting the music become really palpable.” This is a basic requirement for performing C.P.E. Bach in particular. “It’s great making music with people who were pioneers in this field, but who never get stuck in their research and are trying to set new standards with every new recording.” The three concertos in this recording are, in Pahud’s opinion, milestones of flute music:

“When you hear the A minor Concerto, whose beginning is furious to an extent you might find in other works’ finales, if at all, and when you see how virtuosically C.P.E. Bach treats the orchestra and the soloist, you know at once that you’re dealing with a great master who’s aiming to shake the world’s foundations with his music.”

No less revolutionary is the well-known G major Concerto. For Pahud, “even its length, over 24 minutes, is indicative. In those days a flute concerto would last maybe a quarter of an hour. Here Bach is challenging both musicians and listeners to conquer new dimensions.”

The D minor Concerto, too, is risking new musical extremes with its three movements: “In the first movement, the showpiece, we’re dealing with brilliant counterpoint”, Pahud explains. “In the second with an almost transfigured mood, and in the third with a wild, explosive finale. All three works manifest a musical universe that was born at Frederick the Great’s court while also breaking down its strict order — music inspired by change.

Emmanuel Pahud - C.P.E. Bach Flute Concertos is out now.

Emmanuel Pahud takes his French flute revolution to Versailles

October 1789: the French revolution swept through Versailles as an incensed Paris mob stormed the château. Members of the Swiss guard that formed part of Marie Antoinette's entourage of personal bodyguards were killed in their attempts to protect the queen.

These events won't be too far from the minds of many music-lovers at the Palace of Versailles tonight (no 'storming' necessary for ticket-holders), as Swiss virtuoso and Principal Flute of the Berlin Philharmonic Emmanuel Pahud plays concertos from the time of the French Revolution, live at the very epicentre of these historic events.

It's a magnificent setting in which to explore this golden age of flute music that coincided with such political upheaval and drama. With history echoing through the marbled corridors of the palace, the programme will include works by Gluck and Devienne from Pahud's new album Revolution, out this week. Both live at Versailles and on the album, this star soloist is accompanied by his Swiss collaborators the Kammerorchester Basel conducted by Giovanni Antonini.

"In planning this album, I saw the flute concerto as a way of taking listeners on a journey through a period of 30 or so years, centred around the notorious storming of the Bastille in 1789," says Pahud.

Emmanuel Pahud's new album Revolution is out now.

Sound the canons: Emmanuel Pahud's flute revolution is coming this week...

There are many natural resonances between this new album, Revolution, and its predecessor, The Flute King, which celebrated the first golden age of the flute, inspired by the tricentenary of Frederick the Great in 2012. Revolution is devoted to another such high point in the history of the instrument – the years surrounding the French Revolution. The flute of Devienne echoes that of Quantz in Frederick’s day, the music of Mozart’s age that of Bach’s, instead of the monarchy we have revolution, instead of the German school, a French one, and a generation born in the Classical era has succeeded one born in the Baroque, although the two are linked by the Enlightenment and the search for a better world, free from the yoke of earlier generations: a revolutionary ideal.

François Devienne, one of the most striking figures of the Revolutionary period, plays a key role in this new project. A talented composer, as well as a virtuoso flautist and bassoonist, he was so highly thought of that he was nicknamed the ‘French Mozart’. He also helped establish the Paris Conservatoire, and with it a flute school of lasting renown. These considerable achievements are matched by the high quality of the music he wrote for flute, ranging from duets and trios for flutes alone, sonatas with basso continuo or harpsichord and chamber works with woodwind or strings, to concertos and symphonies concertantes, not to mention some of the earliest post-Baroque transcriptions. Finally, his name is closely associated with the Concert Spirituel, the Parisian concert series that played a crucial role in promoting pure instrumental music in a city then in thrall to ballet and opera. Mozart himself was drawn to the French capital in no small part because of the status of the Concert Spirituel. Although a sinfonia concertante for winds missed out on being performed there, his ‘Paris’ Symphony did receive its public premiere at one of these concerts, just a few short years before Devienne’s own debut at the Concert Spirituel, where a number of his contemporaries also appeared, notably other teachers at the Conservatoire.

In planning this album, I saw the flute concerto as a way of taking listeners on a journey through a period of 30 or so years, centred around the notorious storming of the Bastille in 1789. The works featured here bear witness to what was in fact a relatively rapid transition from the style of Gluck, a man of opera and of the Baroque – and whose concerto represents pre-Revolutionary Paris – and the revolutionary and Romantic ideal such as we understand it, sometimes hinted at, sometimes fully embraced. It can be heard, for example, in the inventive and lyrical musical universe of Gianella, a virtuoso flautist who came from La Scala in Milan to try his hand in the new world represented by Paris. Of Austrian origin, the much better-known Pleyel was an extremely gifted musician and pupil of Haydn who owed his survival to the skilful way in which he convinced the Revolutionary authorities that he had left his former royalist connections behind. Having moved to Strasbourg in 1785, it was only after the Terror that he came to Paris, where he did much to promote instrumental music by founding first a publishing house and then the Pleyel piano factory. With both Classical and dramatic elements, his Flute Concerto is particularly well developed and makes formidable virtuosic demands on the performer.

As for Devienne, his E minor Concerto is a standard of the concert and competition repertoire, a work which continually pushes the flautist to the technical limit. It has a dramatic intensity that can be heard in the very first bars of the orchestral introduction, and an eloquent musical discourse that creates superb contrasts in the dialogue between soloist and orchestra.

There is a great deal more music from this period worthy of revival, and we faced a difficult choice, faced with some extraordinarily varied works for ensemble and others for orchestra, notably an exceptionally rich vein of symphonies concertantes. Ultimately, however, I chose to structure an album around these striking concertos, and was lucky enough to find in Giovanni Antonini and the Kammerorchester Basel a group of colleagues to perform this music with spirit and an appropriately revolutionary combative fervour! A quick light-hearted digression into semantics: one of the main meanings of the word ‘revolution’ is ‘going round in circles’ … in other words, you end up where you started, although permanently transformed by the experience – in my case, a musical experience.

The work I’m doing with the ensemble Les Vents Français is aimed at continuing the tradition of the Devienne school, and at bringing about a kind of new revolution, following the examples of Paul Taffanel in the late 19th century, and Jean-Pierre Rampal in the post-war period. It was Rampal too who, throughout his career, rediscovered and recorded many of the works that symbolise late 18th-century Paris, including those featured here. In a way, therefore, this celebration of a golden age is my tribute to the French flute school, in repertoire that I studied at the Conservatoire and whose return to the spotlight is more than overdue.

Emmanuel Pahud's Revolution: new album of revolutionary flute music out in March

Widely recognised as the finest flautist performing on the world stage today, Emmanuel Pahud has joined forces with the Kammerorchester Basel for his new album of flute concertos by composers from the time of the French Revolution. The album, to be released early March, reveals how the form and the instrument underwent their own musical revolution during this tumultuous period.

For Revolution, Pahud delves once again into the history and evolution of the flute in the second half of the 18th century, following the success The Flute King, his 2012 album of music written for and by the Prussian king Frederick the Great, himself a gifted flautist-composer.

Pahud now continues on this path from the dawn of the Enlightenment to the French Revolution, capturing the drama and excitement of the political upheaval that surrounded what was a golden age in music, particularly for the flute. Pahud explains: “For me, this album is about taking you on a journey via three decades of flute concertos surrounding the events of the famous storming of the Bastille in 1789, in what was a rapid transition from Gluck’s musical idiom, shaped by opera and the Baroque – his concerto here embodies Paris before the revolution – to the Romantic and revolutionary ideal that we hear in the music that follows.” This includes concertos by little-known composers François Devienne, Luigi Gianelle and Antoine Hugot.

“In choosing to structure this album around these remarkable concertos, I had the great fortune of having Giovanni Antonini and the Kammerorchester Basel as partners," adds Pahud. "They defend this music with fighting spirit and a truly revolutionary fervour!”

Emmanuel Pahud is Instrumentalist of the Year (Flute)!

November sees the release of Les Vents Francais' new album Winds & Piano (already available in Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Japan), followed by 8 concerts in December.

Related releases

Upcoming Concerts

Friday

Sunday

Wednesday

Thursday

Thursday