Erik Satie

News

Erik Satie, 150 years of the eccentric French composer par excellence!

Erik Satie: The Oldest of the Moderns

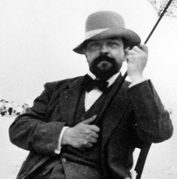

With his unfailingly immaculate detachable collar and his brilliant conversation, Satie delighted the salons of Parisian society and gathered around his bowler-hatted figure with umbrella several generations of musicians from Claude Debussy to Henri Sauguet. His personality quickly took precedence over his music in the public’s perception. Is the situation different 150 years after his birth? The 10-CD complete edition Tout Satie pleads in favour of the affirmative.

Satie was born at Honfleur on 17 May 1866. His mother was of Scottish origin, and his father was a shipping agent; they were Anglican Christians. Torn between Normandy and Paris, the family settled in Paris in 1870. Two years later, Satie’s mother died and his father placed the young boy into the hands of his parents. Six years later, in 1878, his grandmother was found dead on the beach in Honfleur, and so now the 12-year-old Satie returned to live in Paris with his father, who married a young pianist by the name of Eugénie Barnetche. There he took lessons in piano playing, standing out, despite some talent, as a bad student and displaying an equal dislike for his mother-in-law, the instrument and the music.

His disquiet did not prevent him from entering the Paris Conservatoire through a back door in 1879 but only two years elapsed before he escaped with a dismissal: “untalented,” grumbled his teachers, who nevertheless readmitted him to the respectable institution at the end of 1895. There is a somewhat comical trait about this coming and going, rather like a hesitating waltz, that presaged the start of something. In 1884, he composed what appeared to be his first piano piece with the simple title of Allegro - his teachers had been seriously mistaken when they thought the young man definitely had no future in music.

However, Satie decided to take up military service, a blunder that he was soon able to rectify when he developed a serious congestion of the lungs brought on by a deliberate exposure of his naked torso to the cold. It was now 1887, Satie was 21 and had settled in Montmartre. He spent time in cabarets, rubbed shoulders with Verlaine and Mallarmé, composed his Ogives written without bar lines, a style that was to remain one of his signature characteristics, as well as three pieces for piano which were to become the sonic symbol of his work: the Gymnopédies.

Then came the decisive encounter. At the Chat Noir Café-cabaret, he became friendly with Claude Debussy. The first years after 1890 were blessed times: Satie became the "official" composer and choirmaster of the Ordre de la Rose-Croix Catholique. He started to gain renown and he took Debussy along with him on his sweet pseudo-mystical journey.

Faith but also love revealed themselves to him in the features of Suzanne Valadon: she was to sketch her lover with a beard and long hair in a touching portrait. The end of this relationship, unequally shared, was to leave Satie far more broken-hearted than he wanted to admit to himself. Something snapped suddenly in him. Vexations – a short and dry piece "to play 840 times in a row" – might have been a vain outlet.

Satie’s soul was dead but the composer in him continued to live for 32 more years. Obdurately self-willed, his multi-faceted oeuvre was to be characterised by a modal grammar and white colour that lay outside any established trends, but created a trend of its own that was to marginally influence young people: it was to be a constantly present "elsewhere" in the musical landscapes that followed in Paris at the start of the 20th century.

Meanwhile, in 1895 he received a small inheritance that quickly melted away between his fingers, dispersed in editions of his music. It was the only real moment of relative opulence in a life that was soon reduced to poverty, forcing him to remain a cabaret pianist for a long time and attend social dinners in town by paying with his fine words.

So it was that he would go from the cafés in Montmartre to the tiny room in Arcueil where he finally settled in 1897. Here he composed his works ranging from melodies that he called "thorough rubbish", such as Je te veux, to piano pieces with convoluted and hilarious titles such as Embryons desséchés (“Desiccated Embryos”) and other Peccadilles importunes (“Tiresome Pranks”). His scores abound with performance markings swinging between poetic and humorous comments that are intended for the sole enjoyment of the interpreters.

Even so, Satie felt that his compositional technique was not yet fully fledged, and so in the autumn of 1905 he became a pupil of Vincent d’Indy and Albert Roussel at the Schola Cantorum. His friends thought that he was having one of his funny turns, but under his "good masters" Satie blithely learned the strict academic technique of counterpoint. He dressed it up in his own way and Debussy made fun of it by calling him "Mister Counterpoint". So now he was a perfect musician! Was this necessary for his music?

The First World War now introduced Satie to a new generation. In 1915, through Valentine Gross he met Jean Cocteau, who became a kind of mascot for him. Undoubtedly the poet had some affection for the future composer of Parade, although correspondence that is often coloured with spiteful remarks and clashes over "matters of principle" reveals that the idyll was more often than not a bitter one. But this did not really matter in the long run, since on the one hand Satie became the idol of the young musicians – it was around his small goatee beard that le Groupe des Six was gathered together, he became both their backbone and their catalyst – and on the other hand he also became the composer of Parade.

Up to now, the musician of Arcueil had carved his own way mainly with the piano. Parade inspired the fortification of his art. Could Roussel have ever imagined that his orchestration pupil would write a ballet with a siren, a gun and a typewriter?

Parade was Cocteau’s conception – he "sold" the design of the stage set to Picasso before Satie had composed a single note – but it was Satie’s music that was to create the ‘scandale’ that ultimately spelled a glorious success but also eight days in a detention cell for having called the critic Jean Pouiegh an "unmusical ass". And finally on this subject of Parade, Guillaume Apollinaire should have the last word: in the premiere’s programme, he noted the "surrealist" quality of the show.

With this ballet, Satie had taken a leap forward. Well aware of the journey he had taken from the Montmartre cabarets to the European avant-garde, in 1919 he became friends with Tristan Tzara, Man Ray, André Derain, and Marcel Duchamp.

There was not a single musician friend on the horizon: instead he formed an allegiance with the Dadaists. Taking sides with Tzara in 1922 during the famous discord between the poet and André Breton, he had become so indispensable to the futurist movements that Breton, despite his anathema, decided not to sever ties.

In the short time that Satie had left to live, such notoriety did not bring him the financial relief that he could have hoped for. Poverty persisted, but his music made a quality out of it: the whiteness of timbre, the sparseness, the economy, the writing so modest that it became a quasi-abstraction: these were the culminating attributes of what constitutes after Gymnopédies and Parade his third masterpiece.

In 1918, The Princess of Polignac commissioned him to write what would become Socrate, a triptych full of bare and unchecked emotion. Probably for the first time, Satie was completely happy with his work. The laughter he had to endure at the premiere of the orchestrated version in 1920 left him speechless but yet did not destroy his will to compose.

With Jack in the Box, and Mercure, he sought in vain to recreate the success of Parade. He was not left without friends: in 1923 a group from the School of Arcueil brought him a few young people that were followers of Max Jacob, among them Henri Sauguet and Roger Désormière.

In January 1925, Satie fell ill; it was to be a fatal disease. What a surprise for Milhaud when he entered Satie’s Arcueil lodging for the first time after his death to find two pianos tied together by a rope and the room full of unsealed letters testifying to a life of darkest misery. Here, after the composer’s death, they miraculously found Geneviève de Brabant, a score Satie had pretended to have lost– a final jest of his destiny unless, in keeping with his fabled hoaxing, he might have quietly put it away pending its improbable survival.

Jean-Charles Hoffelé (Translation: Michèle Fajtmann).

The 150th anniversary 10-CD boxed set Tout Satie! is out now.

Erik Satie: a surrealist tribute 150 years after the composer's birth

Whether playing piano at Le Chat Noir cabaret or rubbing shoulders with Claude Debussy and Jean Cocteau, Erik Satie was one of the most eccentric figures to wander the streets of Montmartre in the 1890s. Known as 'the velvet gentlemen' for his set of identical grey corduroy suits, he has become as famous for his personality quirks as for his music.

Satie hoarded dozens of umbrellas in his cramped, squalid apartment. He wrote ethereal miniatures for piano entitled 'Pieces in the Shape of a Pear' and 'Flabby Preludes for a Dog'. He founded his own religion. His diet consisted only of white foods. His anti-masterpiece Vexations consists of the same niggling chromatic phrase played on piano 840 times, but with his Gnossiennes and Gymnopédies he also gave us some of the most dreamy, free-flowing and meditative music ever written for piano.

Today's bearded, bespectacled hipsters could never hope to hold a candle to such startling originality.

Warner Classics' Paris offices are just a few minutes' stroll from Satie's favourite hangouts in Montmartre. We pay tribute this year, the 150th anniversary of his birth (17 May), with a very special photo-shoot of 'Satie selfies' inspired by the composer's surrealist iconography and instantly recognisable style. All to showcase the special-edition Satie LP released for Record Store Day this week: the classic 1956 Aldo Ciccolini recording that brought his wonderful, wistful world to a new generation of listeners finally ready for him.

Celebrations are already underway with the first complete boxed set of his music, on 10 CDs: Tout Satie! featuring legendary French performers including Jean-Yves Thibaudet and Alexandre Tharaud.

(With thanks to photographer Zinzi Gugu and Otis the chihuahua).

Limited-edition Erik Satie album to be released on vinyl for Record Store Day

An exclusive re-release for Record Store Day 2016 (16 April), this LP of Gymnopédies, Gnossiennes and other piano pieces by Erik Satie marks the 150th anniversary of the eccentric composer's birth.

It also salutes Aldo Ciccolini, the Italian-born pianist who launched the Satie ‘boom’ when this album first appeared in 1956.

Whether enigmatically serene, irresistibly charming or anarchically witty, the maverick French composer’s miniature pieces remain astonishingly original. His whimsical avant-garde view of the world has inspired artists and musicians from Jean Cocteau to John Cage to John Cale.

At every moment on this recording, Ciccolini makes clear why, when he died in February 2015, The New York Times described him as “a champion of Erik Satie”.

The limited-edition release will be available in a pressing of 1,000 copies only.