Jacqueline du Pré

News

50 years today since Jacqueline du Pré recorded the Elgar Cello Concerto

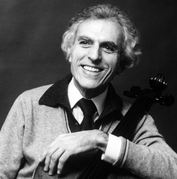

When Sir John Barbirolli recorded Elgar’s Cello Concerto and Sea Pictures in August 1965, he chose two young soloists for whom he had great admiration as artists and much affection as people: the cellist Jacqueline du Pré and the mezzo-soprano Janet Baker. In 1956 he had been chairman of the jury which had awarded the 11-year-old Jacqueline du Pré the Suggia Gift. He watched with interest the development of her career and in 1965 invited her to perform the Elgar with his own Manchester-based Hallé Orchestra.

She had a very free approach to the work and Barbirolli persuaded her to bring a little more tranquillity to her interpretation and not to ‘give out’ all the time. But he admired her temperament: ‘If you haven’t an excess of everything when you’re young,’ he said, ‘what are you going to pare off as the years go by?’ Even so, some dyed-in-the-wool Elgarians felt that their interpretation was not sufficiently ‘stiff upper lip’, a view with which Elgar himself would not have agreed. When the young Menuhin had been criticised in 1932 for robbing the Violin Concerto of its ‘austerity’, the composer retorted: ‘Austerity be damned: I’m not an austere man.’

For economic reasons, EMI booked the London Symphony Orchestra rather than Barbirolli’s beloved Hallé for the recordings of both works. As a youth he had played in the LSO’s cello section in the under-rehearsed first performance of the Elgar Cello Concerto and in 1927 he had conducted the orchestra for the first time, an occasion for which he learned Elgar’s Second Symphony in 24 hours.

On 19 August 1965 they recorded the concerto’s first movement and scherzo almost in one take and the orchestra spontaneously applauded Jacqueline du Pré. The release of the recording was, as predicted, a success, although when she first heard the disc the cellist is said to have burst into tears and said: ‘This is not at all what I meant!’

The Cello Concerto dates from 1918–19, when Elgar was living for part of each year at a cottage in Sussex where he also composed his last three chamber works. He had been ill and was depressed by the slaughter of the First World War, and the concerto has an elegiac, autumnal quality: nostalgia for a world that has vanished. Yet it is also vigorous and in parts of the last movement recaptures some of the swagger and zest of his pre-1914 works. He described it as ‘a real large work & I think good & alive’.

Yet it is the sad serenity of the Adagio and the anguished outburst towards the end of the finale that haunt the listener and are so poignantly interpreted in this recording. Today it ranks among Elgar’s most popular and loved works, thanks in no small measure to this recording.

Author: MICHAEL KENNEDY

Today would have been Jacqueline du Pré's 70th birthday

A tribute to Jacqueline du Pré from renowned music documentary maker Christopher Nupen, written for her Great Recordings 17-CD boxed set.

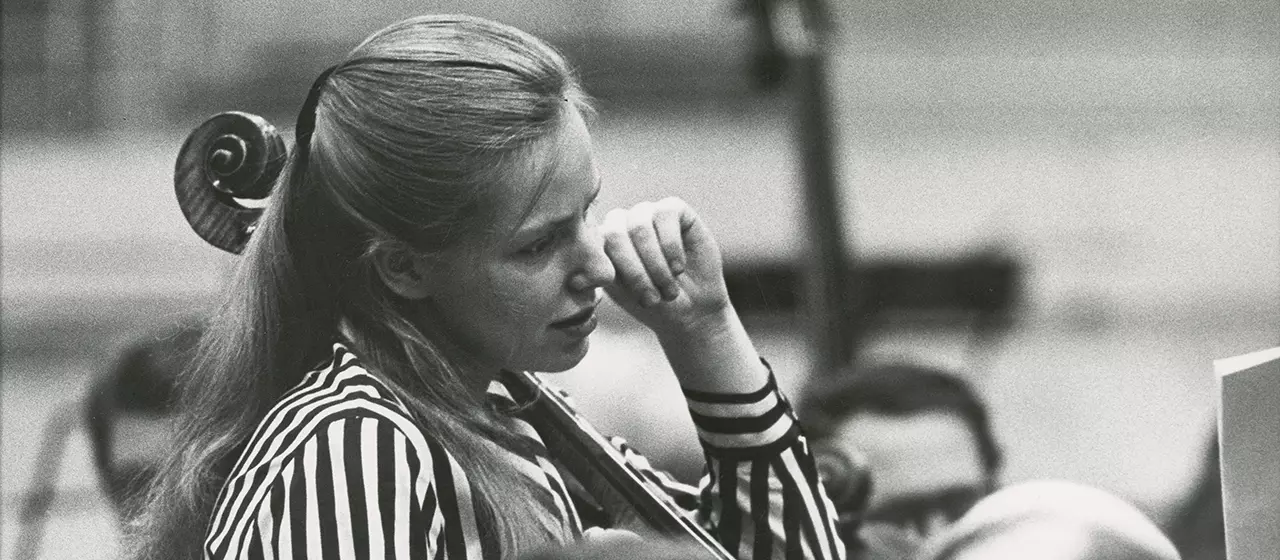

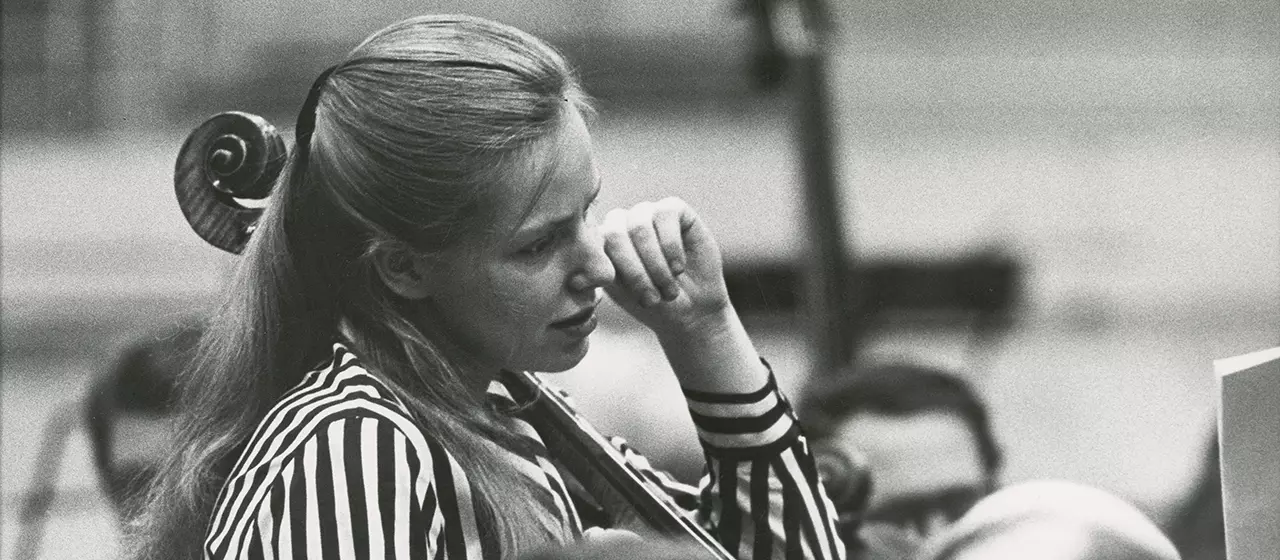

What is it about some artists that keeps their memory alive longer – brighter – in the mind and the heart? Nobody knows all the answers to that question but, for me, the magic starts with the unmistakable, wondrous sounds that they make.

Think of the voice of Enrico Caruso or Maria Callas or Lotte Lehmann, or the sounds that came from Jacqueline du Pré’s cello.

Each, so recognisable, instantly creates an atmosphere somewhere inside us which we remember immediately, is unique, brings with it a heartening sense of warmth and seems to carry a world of meaning – even if we cannot define what on earth that meaning is.

How do you explain it? You cannot. Perhaps because the meaning does not belong to this earth, but to somewhere more elevated, and because the most important part of it has to do with those things in our lives which we cannot explain or understand, beginning with the unfathomable magic of music at its very best.

An artist like Du Pré seems not only to play the notes but to be the messenger of something between the notes or behind the notes, something very elevated that is both personal and universal at the same time and seems, in some inexplicable way, to be for ever.

For many of us the answers also include the strange conviction that, in a way which we cannot define, something of that deeply felt communion, and even of the artist herself or himself, belongs to us personally. That is one of the magical things about the great performers, an ability so to penetrate the heart and mind as to leave the impression that something permanent remains and is ours.

Jacqueline du Pré had just such a gift, and with it she had ways of touching us that are given to very, very few. Her life ended in unspeakable tragedy, but what she gave to the world in the best of her too-few years was a glorious celebration of some of the most heartening things in human existence. Among them was an exceptional generosity of spirit that affected almost everybody who ever came into contact with her.

In the 26 years that I was close to her I never saw anybody come into her presence who did not go out brighter than they were when they came in. She lifted the spirit. As Fou Ts’ong says in our film, Who Was Jacqueline du Pré?: ‘I have always heard in her music the person she is. For me, music never lies. The way she played, the reason why she moves one so much, is because there is something so pure and so truthful in her. I always felt that as a person she was like that. If you look at her, in her eyes, it is the same as when she is with the cello.’

We cannot explain, but we do feel it, we do remember it, we do want to remember it and we can record at least something of it, both in audio recordings and in the films. Happily the two are gloriously complementary. And should we try to explain it? Arnold Schoenberg insisted that all attempts to explain the best in music are likely to do nothing so much as to diminish it. His Viennese contemporary Ludwig Wittgenstein reminds us that man needs to reawaken to wonder.

Jacqueline du Pré was as gifted as any musician I have known to help us to do that. As she herself says in our film Remembering Jacqueline du Pré: ‘It was always a source of wonder that when I put the bow onto the string it made a beautiful sound.’ That is one of her deepest gifts, that sense of wonder. It pervaded almost everything that she did both in her music and in her life.

And of her sounds, as Charles Beare, who looked after her cellos throughout her career, says in Who Was Jacqueline du Pré? ‘I have actually never heard anything like the variety of sounds that she could draw out of that instrument. When she came into a room everything stopped, and when she sat down and played the cello, which, of course, she did in our place a lot, everything stopped there. Work in our workshop where they were repairing things or supposed to be, just stopped. Everybody came to listen because you had to listen to the sounds that she made.’

Or as Pinchas Zukerman, who, as a string player was in some ways the closest to her, says at the end of the same film, ‘The only thing to do is to enjoy the fact that you were able to be there when she did it. Just take it all in and say “Wow! I’m lucky.”’

We are indeed lucky that our phoenix lives again in the recordings and the films. Together they keep her spirit and her music alive in the world in a way that was not possible before the 20th century. -Christopher Nupen

Related releases