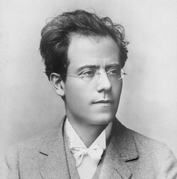

Jean Sibelius

News

Born on this day 150 years ago: Jean Sibelius

Jean Sibelius: Historical Recordings and Rarities 1928-1945. The 7-CD 150th anniversary boxed set is out now.

Although we don’t have more than a glimpse of Sibelius conducting (the Andante festivo, a minor piece from the early 1920s and recorded a few months before the First World War in 1939), we have the next best thing: authoritative performances from musicians and particularly conductors who had brought many of his works into the world, above all Sibelius's fellow countryman Robert Kajanus (1856–1933).

Kajanus himself was a composer of serious ambitions whose output included a Kullervo Symphony, more modest in dimensions than Sibelius’s and a good deal less original. As Sibelius developed in the 1890s and 1900s, Kajanus put his creative work aside and diverted his energies towards establishing his friend on the musical map in Finland and later abroad.

At the turn of the 1930s, perceiving a potentially wide audience for Sibelius's music, EMI engaged Kajanus (selected at the insistence of the composer) to record the First and Second Symphonies, following them up with a wonderfully paced Third and Fifth — part of Walter Legge’s Sibelius Society albums that went on to embrace much of the Finnish master’s work. All of the present performances have the ring of authenticity, as indeed does Sibelius’s final utterance, Tapiola. Koussevitzky’s set with the Boston Symphony Orchestra is enormously powerful, but Kajanus's is even icier and more desolate, his steadier tempo in the final storm of Tapiola lending this evocation of the forest’s power an almost fearsome intensity.

The Kajanus recordings also include the currently neglected incidental music to Hjalmar Procopé’s play Belshazzar’s Feast, not yet surpassed on record. It is a score of delicate colouring with a consistently high level of inspiration — “Solitude” is a piece of outstanding beauty, and “Night Music” is no less elevated and searching. The last movement, “Khadra’s Dance”, with its cool and affecting oboe melody, has a haunting charm in Kajanus’s hands.

Kajanus's close-working relationship with Sibelius was such that his interpretations of the composer's music are today regarded as authentic — indeed, they are considered by many as definitive, comprising nothing less than essential listening for the study of Sibelius. Kajanus certainly set Sibelius on the course to the international popularity, and the dominant position in the Anglo-Saxon world and concert repertoire that Sibelius was to enjoy during the 1930s to '50s was part-cultivated by the allegiance to his cause of major conductors such as Sir Adrian Boult, Sir Thomas Beecham, Serge Koussevitzky, Leopold Stokowski and Sir Henry Wood (who invariably programmed the seven symphonies at London's Proms).

More gramophone recordings from this period attest to his popularity at this time; Sir Thomas Beecham, who had successfully championed Delius in the 1920s and early 1930s and conducted a complete Sibelius cycle in public, made a pioneering set of the Fourth Symphony for the Sibelius Society in 1937, and gave us first recordings of The Bard and the Prelude and a handful of movements from The Tempest — these in addition to recordings of works that are today among Sibelius's most popular: En Saga, Finlandia and the Violin Concerto (with Jascha Heifetz). The Prelude to The Tempest is one of the most brilliant evocations of a storm in all music. Commissioned for a newly mounted production by the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen, which had the resources of a full opera orchestra, it was the last of its kind. The Danes put on a special performance for Sibelius, but strangely (and, perhaps, rather ungraciously) the composer never turned up to hear it.

Other rarities that reached the gramophone during this period were the tone poems Night Ride and Sunrise and The Oceanides, composed shortly before the Fourth Symphony, and the funeral march In memoriam. Night Ride is dominated by a trochaic rhythm which suggests a long journey through a shadowy, constantly changing landscape — the recently formed BBC Symphony Orchestra under Sir Adrian Boult, who were very active Sibelius interpreters, get right to its heart. The Oceanides was commissioned for performance during Sibelius's visit to the United States in 1914, and is not a Nordic La Mer but rather seeks to portray the nymphs of classical antiquity swimming in the streams of the Mediterranean world. It is a work that Sibelius held in great store; Beecham claimed that the maestro himself asked him to record it, and he did so in stereo in 1955, following Boult's earlier BBC Symphony and London Philharmonic versions of the 1930s.

Perhaps Sibelius’s strangest and in some ways most visionary score is Luonnotar for soprano and orchestra. The composer called it a “tone poem for voice and orchestra”, and it is original even by Sibelius’s own standards. Luonnotar is the mistress of the air in Finnish mythology, and the poem tells of the creation of the world, as related in Runo One of the Kalevala. It seems likely that the work was nearing completion in 1910 at much the same time as the Fourth Symphony, since the first performance of “a new tone poem for the Finnish soprano, Aino Ackté”, one of the early exponents of Strauss’s Salomé, was promised for that year. In the end, like The Bard, it had to wait a further three years before its premiere (in Gloucester). The solo part is very demanding, which in part explains its neglect in the concert hall, and Sibelius must have been critical of soprano Helmi Liukkonen as he never passed this 1934 premiere recording for publication. However, it gives a serviceable and more than adequate idea of the challenges it enshrines, also documenting, along with the ensuing Symphony No.6 (another premiere recording which was made alongside that of Luonnotar), another of the composer's proponents and close acquaintances: Finnish conductor Georg Schnéevoigt, who became chief conductor of the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra shortly before Kajanus's death in 1933.

Sibelius's popularity during the 1930s to '50s was such that there was a strong appetite for everything he had written — even weaker pieces like In memoriam and Pan and Echo — and it is fair to say that the major conductors' championing of the large-scale works and their committal to record, as discussed above, encouraged recordings of the composer's smaller-scale works, many of which remain rarities to this day.

In his youth Sibelius had written several quartets, but in his maturity had forbidden their performance; he was adamant in keeping his early scores from the public, most notably the Kullervo Symphony. Voces intimae, a five or rather four-and-a-half-movement work, is a highly introspective work in which the composer crafts a profoundly intimate, even enigmatic, atmosphere. The Budapest Quartet, HMV’s premier quartet, recorded it for the Sibelius Society in 1933. After the war the Griller String Quartet, the leading English ensemble of the day, took it into their repertory.

With Sibelius's music enjoying a new resurgence in popularity of late, today — and especially this year, 2015 being the 150th anniversary of his birth — we are reassessing his place within music history. These early recordings effectively document the consolidation of an early tradition (one that would go on to be refined by various conductors and musicians over the years), revealing the surge in popularity that Sibelius experienced during the last few decades of his life as well as contemporaneous interpretation of his works — some of which clearly adhere to the composer's own interpretation of his music, and many of which have the freshness of discovery found in first performances.

Robert Layton, 2015