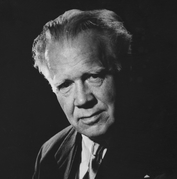

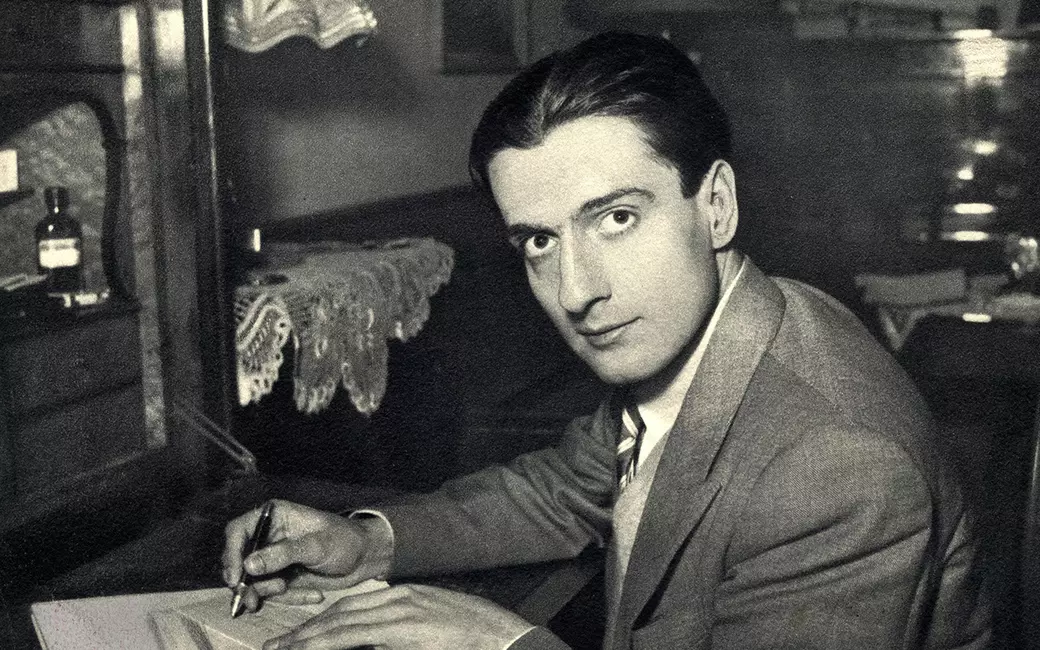

Dinu Lipatti

Über

Speaking in a television interview, the Canadian novelist Margaret Atwood rejoiced in the absence from her novels of human paragons. Even granted their existence, such people, she felt, would make poor or unrewarding characters. Yet had she met and heard Dinu Lipatti (1917–1950) she might well have altered her view. For Lipatti possessed both the qualities of a saint and a richly human nature, and strove throughout his painfully short life for an ever closer identification with his chosen composers. For Yehudi Menuhin he was a "manifestation of a spiritual realm, resistant to all pain and suffering". Cortot thought his playing "perfection", while Nadia Boulanger (Lipatti’s "musical guide and spiritual mother") was haunted, like so many others, by "that serene face with its dark velvet eyes" and the musical clarity and force that emanated from his being. Poulenc spoke of "an artist of divine spirituality", and Lipatti’s close friend and compatriot, the pianist Clara Haskil, wrote to him in wonder and admiration: "How I envy your talent! Why must you have so much talent and I so little? Is this justice on earth?"

Lipatti countered such eulogy with extreme modesty, with comments such as "the concert went quite well". In Haskil’s words he was "a man who seemed embarrassed by his own genius". He fulfilled a startling variety of roles – as pianist, composer, teacher and critic – with tireless devotion and integrity, despite the early and relentless encroachment of the cancer that finally killed him. His compositions are less familiar than they should be, but his classes in Geneva became legendary, and his reviews were as acute as they were sympathetic. Yet it is as a pianist that he will always be remembered. For him the ‘craft of his métier’ was always a blessing rather than a burden and, in exultant reference to the piano, he once exclaimed: "If you only knew how much I love him".

Lipatti’s first serious studies were at the Bucharest Conservatoire, where from 1928 to 1932 his discipline and striving for perfection were already evident. In 1934 Alfred Cortot resigned from the jury of the International Piano Competition in Vienna when Lipatti was awarded only second prize. Lipatti subsequently moved to Paris to study not only with Cortot but also with Paul Dukas and Nadia Boulanger. Though he played Liszt’s E flat Concerto with the orchestra of the École Normale under Cortot in 1934 and gave the Paris premiere of the First Piano Sonata by his godfather George Enescu the following year, his first major Paris recital came later, at the Salle Pleyel in 1939. But the advent of the Second World War obliged Lipatti to return to Bucharest. In 1943 the first signs of leukaemia were diagnosed and although he sustained his professorship at the Geneva Conservatory (1943–46), he reduced the number of his appearances in Europe and cancelled projected tours of Australia and the Americas. In 1946 he signed an exclusive contract with Columbia and, temporarily revived by cortisone, was able to make recordings at his home in Geneva under the supervision of the producer Walter Legge.

Although it is popularly assumed that Lipatti’s repertoire was small, he played 23 works for piano and orchestra and built recital programmes from a selection of pieces by Albéniz, Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, Fauré, Liszt, Mozart, Ravel, Scarlatti, Schubert and Schumann. If one adds to this already extensive catalogue the wealth of chamber music he played with his beloved musical partners Enescu and Antonio Janigro, an image emerges of Lipatti as so much more than a ‘self-effacing perfectionist’.

Lipatti’s final recital, given at the Besançon Festival on 16 September 1950, is one of the great musical and human statements, a testimony to his transcendental powers, his almost frightening assertion of mind over matter. Ignoring his doctor’s advice, Lipatti honoured his last engagement seemingly against all odds, bidding farewell to his adoring public in a unique display of perseverance and musical insight. The only concessions to what his wife described as "a real Calvary" were the omission of Chopin’s Waltz Op.34 No.1 and of a repeat in the Waltz Op.64 No.2. These, together with an occasional hint of coolness (like the settling of some fine but unmistakable frost) in some of the gentler waltzes, are the only evidence of Lipatti’s physical state.

Though these performances have been endlessly discussed and analysed their quality lives on, increased rather than diminished by time. How puzzled Lipatti would have been by the idiosyncratic Bach of more recently celebrated specialists, by the apparent need for intervention; as if the composer needed help rather than illumination. Few performances of the First Partita are more radiant or economical than Lipatti’s. And his Chopin is a truly aristocratic response to music "in which emotion is permitted to suggest itself only through a veil of elaborate civility". Lipatti’s way with the waltzes has justly acquired legendary status. His Schubert Impromptus, too, are flawless examples of his technical and musical regality: the G flat a full-bodied alternative to a more attenuated magic, the E flat with a final touch of defiance rather than deference.

Lipatti, like all truly great artists, remains inimitable. Those who seek to emulate his genius end by sounding nondescript rather than sublime; chastened and compelled to realise that his artistry was an elusive elixir, a subtle amalgam of qualities above and beyond imitation.

Lipatti countered such eulogy with extreme modesty, with comments such as "the concert went quite well". In Haskil’s words he was "a man who seemed embarrassed by his own genius". He fulfilled a startling variety of roles – as pianist, composer, teacher and critic – with tireless devotion and integrity, despite the early and relentless encroachment of the cancer that finally killed him. His compositions are less familiar than they should be, but his classes in Geneva became legendary, and his reviews were as acute as they were sympathetic. Yet it is as a pianist that he will always be remembered. For him the ‘craft of his métier’ was always a blessing rather than a burden and, in exultant reference to the piano, he once exclaimed: "If you only knew how much I love him".

Lipatti’s first serious studies were at the Bucharest Conservatoire, where from 1928 to 1932 his discipline and striving for perfection were already evident. In 1934 Alfred Cortot resigned from the jury of the International Piano Competition in Vienna when Lipatti was awarded only second prize. Lipatti subsequently moved to Paris to study not only with Cortot but also with Paul Dukas and Nadia Boulanger. Though he played Liszt’s E flat Concerto with the orchestra of the École Normale under Cortot in 1934 and gave the Paris premiere of the First Piano Sonata by his godfather George Enescu the following year, his first major Paris recital came later, at the Salle Pleyel in 1939. But the advent of the Second World War obliged Lipatti to return to Bucharest. In 1943 the first signs of leukaemia were diagnosed and although he sustained his professorship at the Geneva Conservatory (1943–46), he reduced the number of his appearances in Europe and cancelled projected tours of Australia and the Americas. In 1946 he signed an exclusive contract with Columbia and, temporarily revived by cortisone, was able to make recordings at his home in Geneva under the supervision of the producer Walter Legge.

Although it is popularly assumed that Lipatti’s repertoire was small, he played 23 works for piano and orchestra and built recital programmes from a selection of pieces by Albéniz, Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, Fauré, Liszt, Mozart, Ravel, Scarlatti, Schubert and Schumann. If one adds to this already extensive catalogue the wealth of chamber music he played with his beloved musical partners Enescu and Antonio Janigro, an image emerges of Lipatti as so much more than a ‘self-effacing perfectionist’.

Lipatti’s final recital, given at the Besançon Festival on 16 September 1950, is one of the great musical and human statements, a testimony to his transcendental powers, his almost frightening assertion of mind over matter. Ignoring his doctor’s advice, Lipatti honoured his last engagement seemingly against all odds, bidding farewell to his adoring public in a unique display of perseverance and musical insight. The only concessions to what his wife described as "a real Calvary" were the omission of Chopin’s Waltz Op.34 No.1 and of a repeat in the Waltz Op.64 No.2. These, together with an occasional hint of coolness (like the settling of some fine but unmistakable frost) in some of the gentler waltzes, are the only evidence of Lipatti’s physical state.

Though these performances have been endlessly discussed and analysed their quality lives on, increased rather than diminished by time. How puzzled Lipatti would have been by the idiosyncratic Bach of more recently celebrated specialists, by the apparent need for intervention; as if the composer needed help rather than illumination. Few performances of the First Partita are more radiant or economical than Lipatti’s. And his Chopin is a truly aristocratic response to music "in which emotion is permitted to suggest itself only through a veil of elaborate civility". Lipatti’s way with the waltzes has justly acquired legendary status. His Schubert Impromptus, too, are flawless examples of his technical and musical regality: the G flat a full-bodied alternative to a more attenuated magic, the E flat with a final touch of defiance rather than deference.

Lipatti, like all truly great artists, remains inimitable. Those who seek to emulate his genius end by sounding nondescript rather than sublime; chastened and compelled to realise that his artistry was an elusive elixir, a subtle amalgam of qualities above and beyond imitation.

Would you prefer to visit our website in English?