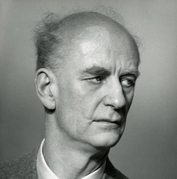

Sir John Barbirolli

Informazioni

Born in London of Italian-French parents, Sir John Barbirolli (1899–1970) trained as a cellist and played in theatre and café orchestras before joining the Queen’s Hall Orchestra under Sir Henry Wood in 1916. His conducting career began with the formation of his own orchestra in 1924, and between 1926 and 1933 he was active as an opera conductor at Covent Garden and elsewhere. Orchestral appointments followed: the Scottish Orchestra (1933–36), the New York Philharmonic (1936–42), the Hallé Orchestra (1943–70) and the Houston Symphony (1961–67). Barbirolli guest conducted many of the world’s leading orchestras and was especially admired as an interpreter of the music of Mahler, Sibelius, Elgar, Vaughan Williams, Delius, Puccini and Verdi. He made many outstanding recordings, including the complete Brahms and Sibelius symphonies, as well as operas by Verdi and Puccini and much English repertoire.

Barbirolli was a late convert to the music of Gustav Mahler. He had first come across it in 1930 when the Fourth Symphony, as heard for the first time at somebody else’s rehearsal, struck him as being thin, certainly by comparison with Berlioz and Wagner. After some early excursions at the beginning of his career – such as in 1931, when he conducted the Kindertotenlieder for Elena Gerhardt at a Royal Philharmonic Society concert in London – Mahler scarcely even figured in his programmes until 1946, when he included Das Lied von der Erde in his third season with the Halle Orchestra. Then in 1952 his friend, the critic Neville Cardus, recalling that Sir Hamilton Harty had given England its first hearing of the Ninth Symphony during his reign as Hallé conductor (1920–33), urged Barbirolli to consider conducting it himself. It was, said Cardus, “the ideal work” for him. Two years later the thing happened: moreover, that first-ever performance by Barbirolli of a Mahler symphony opened the floodgates to a 16-year period in which he embraced them all save No.8. The First, Fifth, Sixth and Ninth he subsequently recorded commercially, and radio recordings of several of the others have also appeared on CD.

The symphonies preoccupied Barbirolli for the rest of his life, possibly even to the detriment of his health, as the vast periods of time he spent studying them had to be squeezed into an already hopelessly overcrowded schedule. He reckoned that mastering a Mahler symphony took between 18 months and two years, and he would spend hours meticulously bowing all the string parts in preparation for his performances. "If you want to conduct Mahler well his music must be under your skin and in your bones", he said, adding: "It is a joy to me in my advancing years that I have found something which […] is of such mighty dimensions. Of course, it does not take two years to read these scores, but if you prepare for a journey through such immeasurably wide musical spheres, you must know exactly where the musical ideas begin and where they end and how each fits into the pattern of the whole […]." To this end he spent several days in 1956 memorizing the choral finale of the Second Symphony, despite the fact that his first attempt upon it was not scheduled until May 1958.

Although a born opera conductor, most of Barbirolli’s operatic conducting was confined to the early years of his career when, between 1926 and 1933, he amassed a repertoire of 20 or so operas while working with the British National Opera, Carl Rosa and Covent Garden companies. Among them was Wagner’s Die Meistersinger, which he toured to the provinces and conducted at Covent Garden: a celebrated souvenir of these performances exists in his 1931 recording of the Quintet with Elisabeth Schumann, Lauritz Melchior and Friedrich Schorr, no less, among the singers. Although he never again conducted the work in the opera house, its overture became a staple of his concert programmes, especially for significant occasions with the Hallé: indeed, in 1943 he chose it to launch the very first concert of the orchestra he had reformed and revitalized in just four weeks.

It was not until the 1960s, during his last decade, that the opportunity to take up again the old operatic scores he loved so deeply came his way. Puccini’s Manon Lescaut and, ironically, Die Meistersinger were among the operas planned for recording by him at this time, but although neither project materialized he did manage to record (besides Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas) Verdi’s Otello – happily bringing the family wheel full circle, as both his father and grandfather had played in the opera’s première at La Scala in 1887 – and Madama Butterfly.

The happy coincidence that Elgar’s Enigma Variations dated from the same year as his birth delighted Barbirolli, and the work became a cornerstone of his repertoire. He conducted it zealously all over the world, and it is a measure of his love for the music that even as late as 1969 he could still write to his friend Michael Kennedy: "I hadn’t done the Enigmas for some time and was completely bowled over by them again." He recorded the work twice on 78s, and twice more during the stereo era, in 1956 and 1962. Completely memorable accounts of Elgar’s Symphony No.1 and Introduction and Allegro date from this period, and this 1956 version of the Enigma Variations, delicate, noble and thrilling by turns, is unquestionably in the same category. His cultivated reading of Ma Mère l’oye, too, reveals a master conductor at work, with an equally fastidious ear for the French repertoire; he and the Hallé were at the peak of their association at this time, with the players wonderfully attuned and responsive to his artistic imagination.

Barbirolli's current EMI discography is extensive and comprises all of his great recorded performances, many in the British Composers series.